Today—National Beer Day thanks to the crusading temperament and social media savvy of Richmond, Virginia’s Justin Smith—doesn’t mark the anniversary of Prohibition’s demise. But in 19 U.S. states it does mark the historic return of beer. Beer of 3.2% alcohol, anyway. But on April 7, 1933, suds of that potency had not been (legally) seen in America for 13 long years. And it was reason to celebrate.

Today—National Beer Day thanks to the crusading temperament and social media savvy of Richmond, Virginia’s Justin Smith—doesn’t mark the anniversary of Prohibition’s demise. But in 19 U.S. states it does mark the historic return of beer. Beer of 3.2% alcohol, anyway. But on April 7, 1933, suds of that potency had not been (legally) seen in America for 13 long years. And it was reason to celebrate.

Wait. How is it possible to have legal beer under Prohibition? You know—constitutionally? Wasn’t the 18th Amendment still part of the supreme law of the land? And wouldn’t it be for another eight months?

Well all that’s true. But arguably, the legislative action exercised in the “Cullen beer bill,” signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 22, 1933, placed the manufacture, sale, and transport of beer into a legal Twilight Zone.

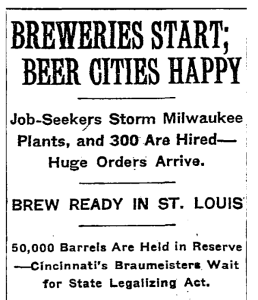

Even as cold boilers were being fired up in St. Louis and Cincinnati, and brewmasters were installing multiple new telephone lines to handle all the orders pouring in, the constitution still technically labeled beer a “prohibited” “intoxicating liquor.”

But no one in the federal government had had any right—any legal, jurisdictional standing—to prohibit alcohol. Not all the way from the Washington administration (starting in 1789) to Woodrow Wilson’s (who took office in 1913, 6 years before Prohibition took affect in 1920). This was a new power delegated to congress. And it took ratification of the 18th Amendment, whose Section 2 did the dirty work, to confer beer-blocking power upon that august body.

But congress, having the power of enforcement, could simply choose not to exercise its control. It effectively chose to give up its power. Or part of it. And that’s what it did with the passage of the Cullen-Harrison Act.

For a country demoralized by a decade of spotty and hypocritical enforcement of Prohibition and terrorized by organized crime selling bootleg booze and “wildcat” brew at exorbitant prices (and sometimes with noxious, supply-stretching additives too), it was certainly the right call.

And let’s not forget what Roosevelt thought most important of all: the shot in the arm the reopening of a major industry could give to a middle- and working-class population deeply mired in economic depression. The very same day FDR signed the bill, such a mob of job seekers descended on the breweries of Milwaukee that the police had to be called to keep order.

In Chapter 7, The Comic Book Story of Beer immerses us fully in the colorful yet frustrating period of American history when anti-alcohol “dry” politicians ruled the day. What the book doesn’t have the chance to get into, however, is a more detailed, granular exhibition of how April 7, 1933 played out. So in light of our dedication to beer’s history in and out of the pages of The Comic Book Story of Beer, let’s take a look at some contemporary reports of that happy occasion.

We’ve already labeled this period of American history “frustrating.” And exultant as the day should have been, that is exactly what many beer drinkers found April 7, 1933 to be as well!

We’ve already labeled this period of American history “frustrating.” And exultant as the day should have been, that is exactly what many beer drinkers found April 7, 1933 to be as well!

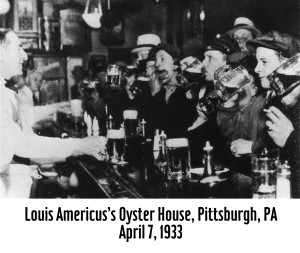

Fully-stocked trucks and trains left breweries around the nation at exactly 12:01 am. But there were still mucho delays getting ales and lagers to their destinations. Many folks didn’t get beer when and where they wanted it. These had to become “beer pilgrims”—driving sometimes hundreds of miles searching for a drink.

Now just because old FDR had signed the beer bill doesn’t mean that the country had kicked the federalism habit. You know, that thing about governors, judges, and state legislators having power in certain spheres where Uncle Sam can go pound sand. Prohibition, after all, had started in the states. And many states in 1933 (and beyond) retained the power to remain “dry” if they chose.

So many of the nation’s beer-thirsty—especially in the South, where the urge to prohibit had been strongest (beer was such an urban, Catholic, immigrant thing after all!)—had to cross state lines if they wanted a taste. Alabama was a no-go. North Carolinians would have to wait until May 1 because the boys over in Raleigh didn’t get their act together in time. (A similar situation played out in Massachusetts).

Still-dry West Virginians largely faced a choice: grab a brew in Ohio or Kentucky. And on what we might call the first National Beer Day, those who picked the Bluegrass State came up short-handed.

According to the Charleston, West Virginia Gazette, the border town of Catlettsburg, Kentucky, had been infamous for beer-swilling in the old saloon days. Eager to get off the wagon again, Catlettsburg’s merchants had dispatched drivers to Louisville. Only later did they hear that the trucks got stuck in long lines at brewery loading docks waiting to be filled up. West Virginians who had headed to Irontown, Ohio, were the ones who had a chance to fill their steins. (The good news for West Virginians, though, was that a shuttered glass factory in Wheeling was going to open again to take advantage of a massive call for bottles).

Drinkers in more enlightened areas—like Maryland, Illinois, Wisconsin, Arizona, California, and Oregon (which only boasted two breweries at the time!)—had their own frustrations and challenges.

Breweries had only been online for just over two weeks, and the supply simply couldn’t meet demand. Washington state, according to the wire services, “drank itself dry before noon.” In Los Angeles, all the beer was consumed plus a million and a quarter bottles brought in from outside the city. In San Francisco, brewers dared to hold back a reserve supply as gangs literally pounded on the doors. “The situation has passed the point of human endurance,” remarked Max Koehnm secretary of the California Brewers’ Association.

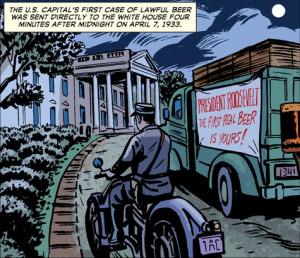

The Comic Book Story of Beer depicts the many cases of beer sent to the White House from grateful brewers in the District, Baltimore, and Wisconsin. FDR, however, diplomatically gave all the brew away. Most of it was spilled down the gullets of members of the National Press Club.

A Canadian newspaper was the only one I found mentioning a CBS radio program celebrating the return of beer that day. Reflecting a sentiment that many, say, French and Poles would be expressing twelve years later, a song called “Thank You, Mr. Roosevelt!” was performed. Now chasing down a recording of that would be one hell of a beer history treasure hunt!

Organized crime, for whom Prohibition had worked out so well, evidently weren’t thrilled by the development of re-legalized 3.2% beer. A bomb—believed to have been the work of a gangland thug—was thrown at the Prima Brewing Company in Chicago on April 7, 1933. The explosive caused no deaths or injuries but inflicted a reported $1500 in property damage.

Organized crime, for whom Prohibition had worked out so well, evidently weren’t thrilled by the development of re-legalized 3.2% beer. A bomb—believed to have been the work of a gangland thug—was thrown at the Prima Brewing Company in Chicago on April 7, 1933. The explosive caused no deaths or injuries but inflicted a reported $1500 in property damage.

Drinkers in Middlesboro, Kentucky, weren’t sure the beer they got was really 3.2%. A Tennessee man who had made his own crawl over state lines was said to have pounded 30 beers—and was still standing. Reporters reported him going back to the saloon for #31.

Other than the mob, the drys, and the beer desirers who didn’t get any (or didn’t get enough) that day, you know who else was feeling pain on April 7, 1933? According to reports, a crisis had come to the cantina operators of Tijuana, Mexico. All through Prohibition American tourists had hopped the border to swill cerveza. But now there was no need. Bars in Tijuana were closing, and an appeal went out to Governor Augustin Olachea of Baja California Norte to do something for the “salvation” of the city.

One thing just about every commentator, city beat writer, and wire service reporter was in agreement on about April 7, 1933? That public intoxication levels were, if anything, lower than usual. The number of arrests for public drunkenness in the San Francisco Bay Area were “normal” according to police.

Within a bay area on the distant far side of the mainland—the Chesapeake—a wordsmith attested, “I saw [beer] drunk by 325,00 Baltimoreans, male and female, without a single casualty, whether moral or anatomical. The hospitals had no business and the cops stood by in amazed enchantment, like Cortez on his peak in Darien, watching the return of common decency to America.”

NOTE: This story also appeared on thecomicbookstoryofbeer.com